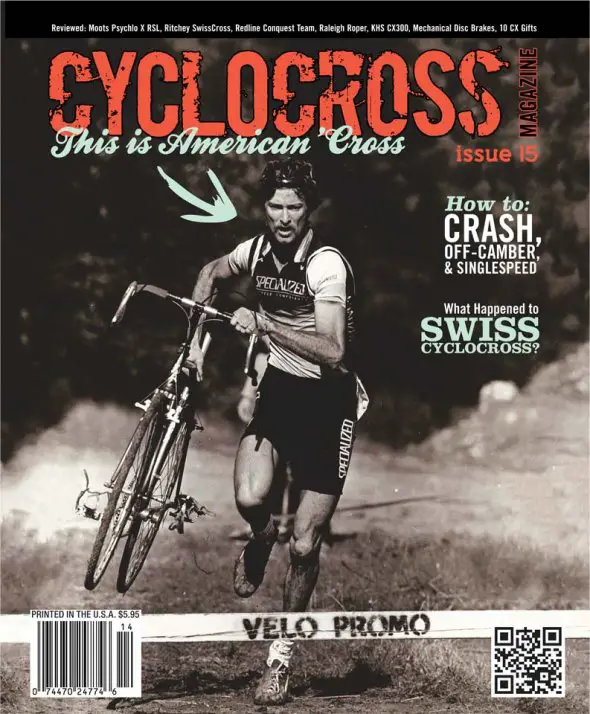

Here’s an excerpt of our much-heralded Issue 15 feature on cyclocross legend and National Champion Laurence Malone, written by regular contributor Robbie Carver.Laurence Malone was the first American cyclocross legend. So how come you’ve never heard of him?

On a cool autumn afternoon in 1962, nine-year-old Laurence Malone sat on a hillside in Berkeley’s Tilden Park. He had ridden there with Betty, a close family friend. Next to Betty lay her 1951 MacLean Featherweight, a 22-pound bicycle made from Reynolds 531 tubing with ornate Nervex lugs. It had a four-speed Benelux derailleur and 650B wheels. Betty and her husband had ridden matching Featherweights across Europe in the company of Laurence’s parents. It was on that bicycle tour that Laurence was both conceived and—in London nine months later—born.

Perhaps Betty had made up her mind to give Laurence the MacLean when she asked him to come on a ride with her, or perhaps the decision solidified only as they sat in silence, looking out over the wooded hills. Regardless, in the very same park that he would, 13 years later, dance away from his competition to win the inaugural USCF Cyclocross National Championship, Laurence Malone, the first king of American ’cross, wiped the tears from his face and accepted his first real bicycle.

That Championship victory in 1975 was no fluke. From 1975 through 1979, Laurence Malone dominated the nascent sport of American cyclocross, reigning the Northern California scene and winning the national title for five consecutive years. For Elite men, that record remains unbroken to this day. “As far as I know,” says Dannie Nall—arguably the man responsible for bringing ’cross to the U.S. and certainly the man responsible for bringing Laurence Malone to ’cross—“from his first cyclocross race on Mt. San Bruno he rode and won until he retired as a Senior, I never beat him.”

“The race was for second in most races he was in,” says Clark Natwick, four-time cyclocross national champion. “He was such a natural at it. He was tenacious. He was tall, lean; he could exploit hills easily over his competition.”

Jim Langely, a Santa Cruz local and mechanic, adds, “Obstacles never seemed like obstacles to him. He had ballet-like grace on the bike. He could get over anything; he could ride over what everyone else would crash on.”

Malone had been racing cyclocross for less than two months when he found himself in Switzerland, at the time when Switzerland was for ’cross what Belgium is now. [See our feature on Swiss cyclocross also in Issue 15]. A complete rookie, he lined up against such giants as Albert Zweifel and Klaus-Peter Thaler.

He did not beat them. But he did catch the eye of the German national coach, who reportedly approached Malone’s coach, Eckhard Rieger, and said, “Give me that kid for a year, and I’ll make a world champion out of him.”

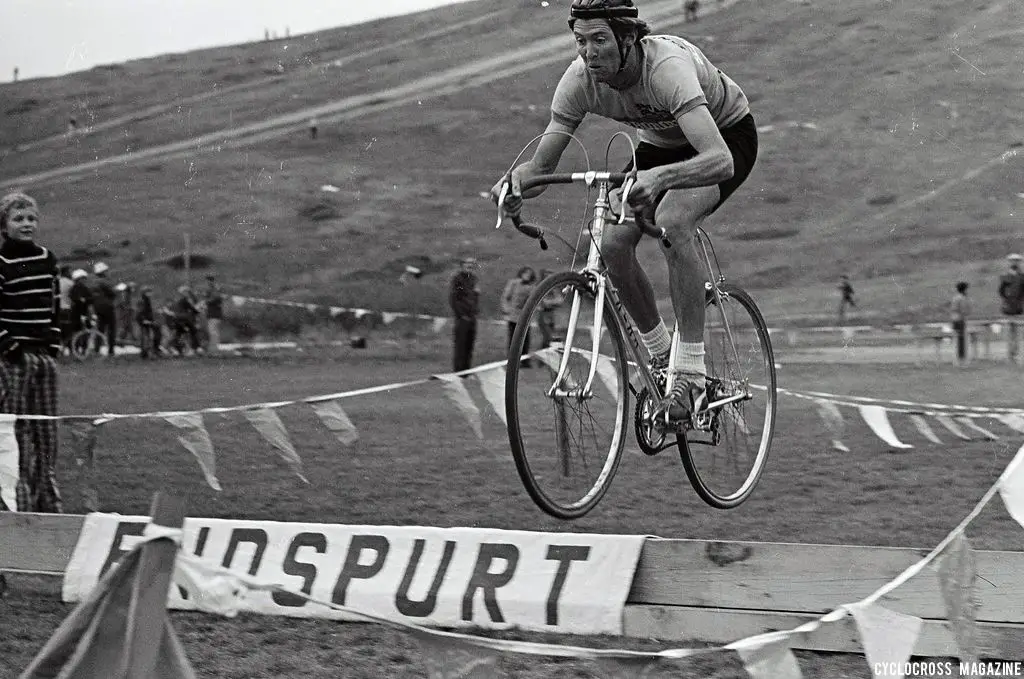

“If he had stayed, he would have been the first Tim Johnson, Matt Kelly or Jonathan Page,” says Nall. “He had no coaching whatsoever. He had that kind of motor.” Though Malone did not stay in Switzerland, he continued to return to Europe each winter for the next five years, slowly working his way up the rankings and earning European fame for his ability to bunny hop barriers—a feat no one in the old country had accomplished.

“He was the first American not to get lapped in a World Championship,” says Geoff Proctor, director of Euro Cross Camp, of Malone’s 1977 performance in Hanover, Germany. “That’s to this day a goal that any Elite rider has.”

In the U.S. he was called ‘The Technician’ and ‘The King of Cross.’ In Europe, his bunny-hopping exploits earned him the names ‘Der Springer’ and ‘The American Kangaroo.’ By the ’90s he’d been dubbed ‘The Grandfather of ’Cross.’

“He was a cyclocross specialist when the sport almost didn’t exist,” says 1985 national champion Paul Curley. “Guys like Steve Tilford, they won because they could do something else really well. Laurence won because he was a good cyclocross racer.”

As a writer for VeloNews and Bicycling, Malone perhaps did more than any other to spread knowledge of cyclocross to the broader cycling community. In his reports of the World Championships, his coverage of Nationals and his articles on ’cross skills, Malone’s style was elegant and humorous even as he strove to educate. “His articles talked to me personally,” says Redline’s Tim Rutledge. “He didn’t talk about what equipment to buy; he was always talking about ways to make what was out there work. No one else was doing that. There’s stuff in there that I still use to this day.”

In 1980, Malone retired from racing and spent the next year wandering through South America. He was 26. On his return to the U.S., he coached the national cyclocross team, taking Paul Curley, Steve Tilford, Clark Natwick and Tim Rutledge to Europe in ’83. As a racer, he returned briefly in 1984—primarily as a mountain biker for Specialized—then disappeared again for another five years.

At the 1990 Nationals in Bremerton, Washington, Laurence materialized to easily win the Masters 35+ title. Reporting for Winning, journalist John Pratt wrote that Malone “seemed more apparition than mortal, his unshaven legs and plain, solid-colored jersey a striking contrast to the slick look of oiled muscles and tailored sponsorship all around.” Twenty minutes after the Masters race, Malone jumped into the Elite field and took third against defending champ Don Myrah. Malone, like chess master Bobby Fischer, had returned from obscurity to show the country he was still one of the best in the business.

Such exploits are par for the course with Malone. Stories of him—on and off the bike—all contain a hint of the mythic. That he gestated to the rise and fall of his mother’s pedal strokes seems like the kind of birth story crafted by overzealous disciples, yet strange tales accompany Malone like moths around a light: he rode with a pacifier tied to his seat post; he lived for a year in a teepee; he hitchhiked to the Olympic training center in Colorado Springs—showing up to coach the national team wearing a Mexican poncho and carrying a box of avocados. He stole food and slept under overpasses while trying to make it as a racer. In restaurants, he ate off other racers’ plates and asked strangers if they were going to finish their meals. He once spent 14 days in a PLO prison after illegally entering Beirut in pursuit of a woman—and thought the food delicious.

“If you were going to make a movie of cyclocross,” says Tim Rutledge, “Malone’s who I’d make a movie about. He was the original rebel—he is American ’cross.”

After his incredible performance at the 1990 Nationals, Malone halfheartedly raced another few years before falling back into mystery. The other harbingers of U.S. ’cross are still active in the cycling world: Clark Natwick coaches and races in the Bay Area; Steve Tilford lights up Masters fields; Tim Rutledge started the Portland Metro series, which evolved into the Cross Crusade, and is the man behind the ubiquitous Redline cyclocross line. Jim Gentes founded Giro helmets and Dannie Nall has worked for Specialized and Raleigh. These athletes have not yet faded into legend.

Malone has.

“Last I heard he was in the Southwest somewhere,” one person told me. “Do you even know where he is?” I heard from another. “Does he have a roof over his head?” asked a third. If cyclocross has a map, Malone fell off of it long ago.

I was off to Chumayo, New Mexico to find him.

“That you even found him,” Rutledge says, “is a bit of a wonder.”

To read more about this legend and Carver’s adventuresome journey to meet him in person, check out our back copy and subscription options on uberflip.com. For less than one race entry fee, you’ll get hours of cyclocross entertainment, eye candy and education without any of the pain of a race.