Cutting Edge Injuries, Giant Handshake Bruises

As mountain biking was exploding, Paul Component Engineering was well positioned to take advantage. Paul’s brakes and brake levers were the must-have item, and the company looked to the next frontiers: shifting and OEM components.

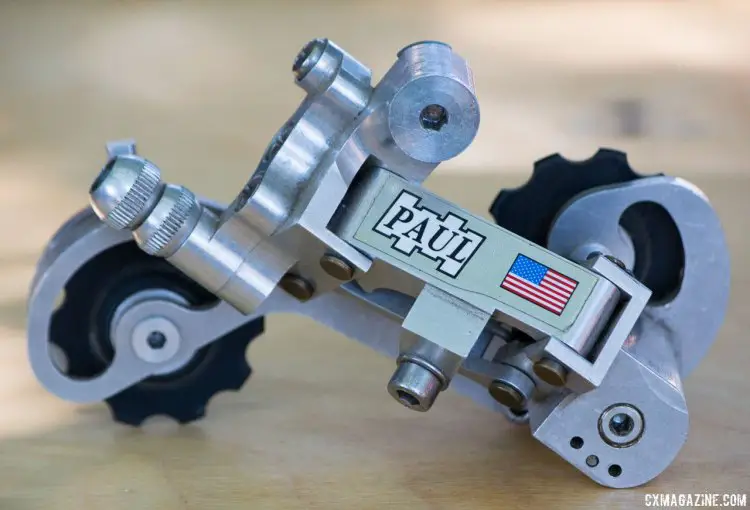

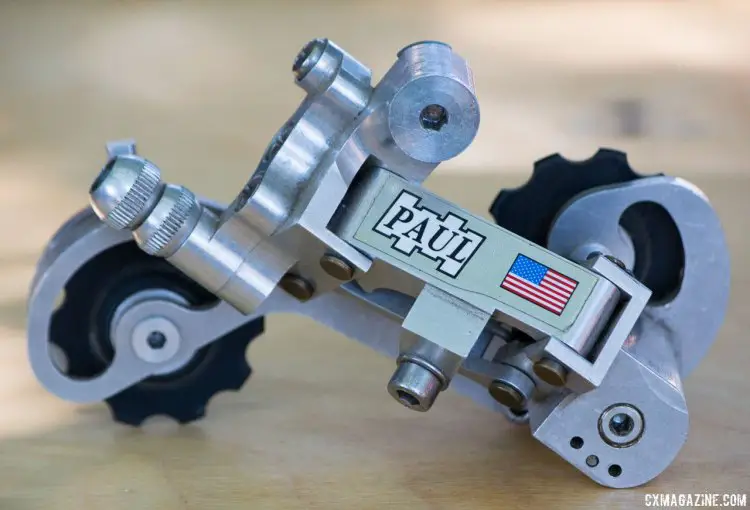

Price dedicated his attention to derailleurs, both front and rear, and developed an intricately machined rear derailleur that many of us lusted after the moment we saw it. The derailleur featured machined pulleys, Allen key limit screws and a beautiful thumbscrew for cable tension. There was demand for the expensive, high-end item, and about 1,500 units made their way throughout the world, but there was a Japanese giant lurking in the shadows.

The Paul Component Engineering derailleur is a symbol of engineering pride and also a distinct turning point in the company’s history. © Cyclocross Magazine

Meanwhile, bike companies started calling. Trek wanted Paul Component Engineering to provide a braking solution to its full suspension Y-bike that didn’t have a cable hanger. Paul obliged, and says initially he was so flattered the Wisconsin company wanted to work with him that he didn’t price his components appropriately and lost money.

Bianchi called too, wanting Paul hubs on its B.O.S.S. and B.U.S.S. singlespeed mountain bikes, but they weren’t sold in high numbers.

The biggest challenge emerged from Japan. Shimano’s second-generation XTR M950 appeared in 1996. With V-brakes, a splined bottom bracket and crankset, and a grey finish that distinguished it from anything else Shimano had made, second generation XTR effectively ended the CNC era, and Paul Component Engineering was not immune.

Even with the continuing Bianchi deal, Paul Component Engineering wasn’t selling much of anything a few years after the M950 launch. Price needed to evolve, and in 1999, looked to focusing on frame building. Knowing the CNC machined aluminum nature of Paul Component Engineering, you’d think the frame would maximize use of CNC machined aluminum pieces, perhaps like an aluminum Manitou frame. However, Paul stayed true to his roots of drop bar cycling, and built a cantilever-equipped, cyclocross-like brazed steel rig he called the Super Commuter. The high-end commuter bike was a novel concept and a versatile option, but they took forever to build, and he stopped after making just seven, never officially selling any.

Paul briefly attempted to focus on frame building in 1999 with this brazed steel Super Commuter model. Seven were built, but none sold commercially. © Cyclocross Magazine

The frame building diversion capped a low moment for Price. His business was struggling as was his personal life—stresses that even pulled him off the bike. It’s an all-too-common story of a passionate cyclist dedicating himself to the cycling industry to the point that he doesn’t ride.

Continue reading as Price returns to his riding roots.